Like my last post, lots of short stories. Hopefully another full post is coming soon.

1. I like chocolate now.

Whhhhhhhhhaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaat? I know. I don't even know what to do or where to begin. I have so many years to catch up from.

Ok, Parents – I know you're reading this. Take a deep breath. I AM ACTUALLY YOUR CHILD. There is no more question about it. I feel like I finally joined the family I've just been pretending to be a part of for the last 21 years.

Can I say it again? I think I like chocolate. Weird.

It all started about three weeks ago, the week before our Spring Break. Lynn, our anthropology professor, is also a star baker and has baked a cake of some sort for every birthday thus far on the program.

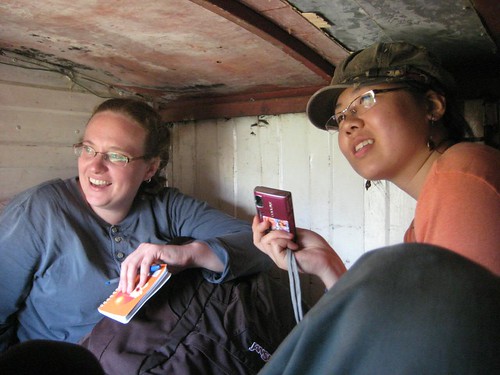

It was Haeinn's birthday, and Lynn baked an oatmeal chocolate chip cake. After singing, we're all standing around talking and a piece of the cake gets placed in my hands. I didn't want to be rude, and telling people that yes, I really don't like chocolate has gotten pretty tiring after a decade and a half, so I said thank you and graciously accepted the slice.

I took a nibble, and realized that I didn't hate it. I took another one, trying to break the one-chew-avoid-the-tongue-and-swallow habit I have had so long to build up, and the damn thing wasn't that bad.

I asked Lynn – It didn't have too much chocolate, she said. I chalked it up to her amazing baking ability and moved on. In hindsight, though, that cake played a pretty important role in my life. So, mom, if you're looking to make me a homecoming surprise:

Oatmeal Chocolate Chip Cake

1-3/4 cups boiling water

1 cup oatmeal, uncooked

1 cup brown sugar, lightly packed

1 cup white sugar

2 large eggs

1-3/4 cups flour, unsifted

1 tsp. Baking soda

½ tsp. Salt

1 Tablespoon cocoa

12-oz package semi-sweet chocolate chips

¾ cups nuts, chopped

½ cup margarine

Mix the oatmeal, margarine and sugars together. Pour in the boiling water and let stand for 10 minutes. Add the eggs and mix well. Sift the remaining dry ingredients together and add to the sugar mixture. Add about one half of the chocolate chips and mix well. Pour into a 9 x 13-inch greased and floured cake pan. Sprinkle remaining chips and nuts over the top. Bake at 350 degrees for about 40 minutes. Test by using wooden pick inserted in the center.

Moist, delicious, freezes well.

From Great Plains Cooking, P.E.O. Chapter AA, Wray, Colorado

Can you tell she's a Doctor of Anthropology? I don't think I've seen anyone cite the cookbook before.

Anyway, the real surprise came on Saturday morning of Spring Break. Jesse and Genna had borrowed Lynn's inlaws' kitchen to cook a cake for Jim, our professor who two days earlier had his laptop stolen on the bus from San Jose, and some brownies for the road trip. I had a brownie on the bus as we drove away from Monteverde, and I liked it. I liked a brownie.

Dave's parents are in town this week, and last night they took a couple of us out to dinner. For dessert, Quinn and I ordered a slice of chocolate torte with guava. It was the first time I have ordered chocolate in... ever. Literally, probably.

I am a new man.

2. One Crazy Floridian

There's a small hotel near my house with wireless internet where I go work sometimes to work on the weekends when I don't feel like walking forty five minutes to get to the Institute. The truth is, I hardly get any work done when I go there, because I spend most of my time either talking with the tourists who stay in the hotel (and, if they ask, dispensing advice about restaurants and how to make the hot water work in the shower), hanging out with Freddie and Marlene, the owners with whom I have traded a bit of tech support for occasional internet use, reading online news, or skyping with people from home.

Last Sunday, however, my unproductivity was made especially special by a wonderful tourist from Florida. It was her last day in Monteverde, and she had about twenty more minutes to wait for her 2:00 PM shuttle to take her down the mountain. Probably in her early fifties, she was traveling alone in the middle of a three month Costa Rica tour. She plopped down next to me, open container of boxed merlot in hand, and due to how far she tilted her head back when she drank while we spoke, the liter had to have been pretty close to finished off.

I mentioned that I was planning a trip down to Chirripó and the Osa Peninsula, both in southwest Costa Rica, and she quickly began to tell me stories about her time on Osa.

First, the mangroves – she said – you must see the mangroves. The best way to do it is by renting a kayak and taking them out on the river, assuming you don't get lost among the meandering pathways through the ten foot tall grasses. She, however, had had no problem on her trip, because she is from Ft. Lauderdale, where there are lots of mangroves. In that part of Florida, she said while making a kayaking motion with her hands (the left still armed with the box of merlot), that's how they get around.

Second, the bug bites. Beware of the bugs on the Osa Peninsula, she told me, wear 100% DEET and rub it all over your body. She had used bug spray, but only as she did in the rest of the country – on her neck and arms and legs, the only exposed parts of her body. In Osa, though, that had not been enough. As she began to explain the consequences of her underuse of repellent, she paused. I'm not quite clear what story she had been about to tell, but all she chose instead to say was, “let's just say I got bites the size of [holds up her fingers in a circle slightly bigger than the size of a quarter] in the white places of my body I don't want to discuss.” We call that good imagery.

3. Quetzals & Other Birds

I saw my first quetzal two weeks ago. And my second, third, fourth, and fifth. I hiked up behind the Institute with Michael, a guy from the States who is doing research down here, and Hillary to a tree where they are known to hang out. When we arrived, we found four males and a female eating wild avocados maybe twenty feet from us. It was amazing. The truth is, they're pretty weird birds – their heads are oddly small, they look like they have little spiked mohawks, and their long split tail feathers look like the tail of a kite. But they are beautiful birds – I can see why the quetzal has been the flagship species for about a dozen different Monteverde conservation campaigns. Here's a picture (not mine – I didn't have my camera with me), but just know that it doesn't do it justice.

I tried to go again a few days ago, but we took a wrong turn and ended up at the house of the owner of the property where this tree sits, who kindly asked us to leave. Hopefully he'll forget me by June, so I can go again before I leave.

In general, birds here are spectacularly beautiful, even the common ones that show up everywhere. Their constant calls may be the one thing I miss most when I go back to the States. Wherever I am here, walking on any road, I can hear birds singing.

I spent a day last week sitting behind Stella's, the bakery near the Institute, taking notes on the behaviors of different species of birds at a feeder for my ecology course. In under an hour, I saw Emerald Toucanettes, Blue Crowned Mott Motts, a Great Kiskadee, and a bunch of Costa Rica's national bird, the Clay-Colored Robin.

A Blue crowned Mott Mott at the Stella's Bakery feeder.

Also last week, I was struck as I sat in class, zoning out for a moment (or two) and hearing a bird singing immediately outside the classroom. As I compared that moment to taking the final exam in Dr. Roth's Intro to IR class my Freshman year, during which a bird repeatedly flew itself head on into the window of the classroom, I remembered just how lucky I am to be here. And it was all I could do not to laugh.

4. Great Saturday

Yesterday, briefly, before I go try to do homework:

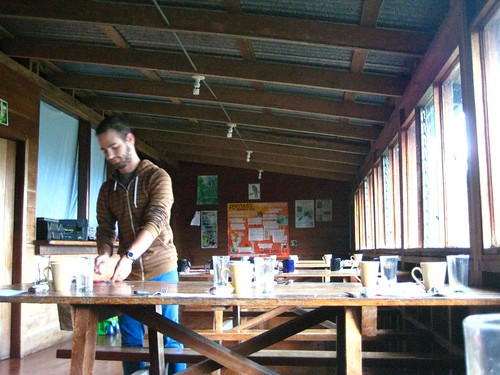

Ultimate Frisbee at the Quaker School. They do it every Saturday at noon, and usually its a good mix between "big people" and "little people" playing together. Yesterday was almost entirely little people, with one or two big people on each team. Anna, a science teacher at the Cloud Forest School, played Ultimate before she graduated from Swarthmore last year and was on the other team - we did more coaching then playing, and it was awesome.

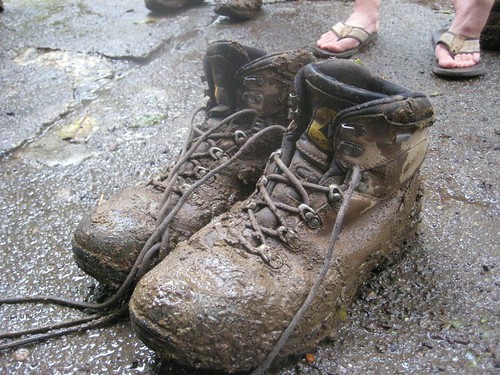

Tried to do homework at the Institute in the afternoon, but Katie's homestay dad and Molly's homestay brother were cutting down a tree and it fell the wrong way, into the road and onto a phone pole. The whole city lost power, phones, and internet for the afternoon, complete with a small explosion and some blue flames. We couldn't do any work, so a few of us hiked to a nearby waterfall and hung out for a while. The power was still out as we walked back, so we stopped in Stella's Bakery for pastries and cheered when their lights came back on as we ate - the guy behind the counter looked at us like we were lunatics.

Went square dancing with Elise at the Quaker meeting house, which I definitely haven't done since they forced us to in Middle School. Officially, it was English Country Dancing - I felt like I was in "The Three Muskateers" and it was great.

Good day.